This autumn FireEye’s FLARE team hosted its third annual Flare-On Challenge. Flare-On is purely reverse engineering based CTF targeting malware analysts and security professionals. This year there were ten challenges and even though all very different, most of them were crypto related.

This post will present my solutions to all the challenges.

I don’t go into a lot of detail in most of the solutions and mostly just present the general idea of the individual challenge. If you are interested in a very detailed explanations, you can check out the official solutions here.

- Challenge 1 (challenge1)

- Challenge 2 (DudeLocker)

- Challenge 3 (unknown)

- Challenge 4 (flareon2016challenge)

- Challenge 5 (smokestack)

- Challenge 6 (khaki)

- Challenge 7 (hashes)

- Challenge 8 (CHIMERA)

- Challenge 9 (GUI)

- Challenge 10 (flava)

Challenge #1

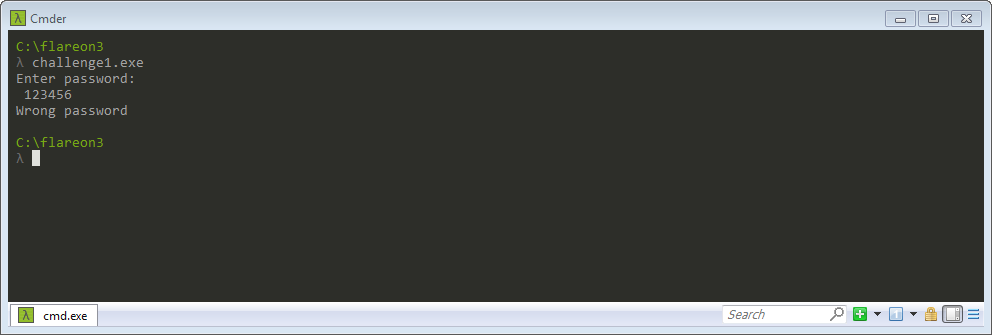

Challenge1.exe is a standard win32 console application which asks for a password (presumably our flag) and prints a message:

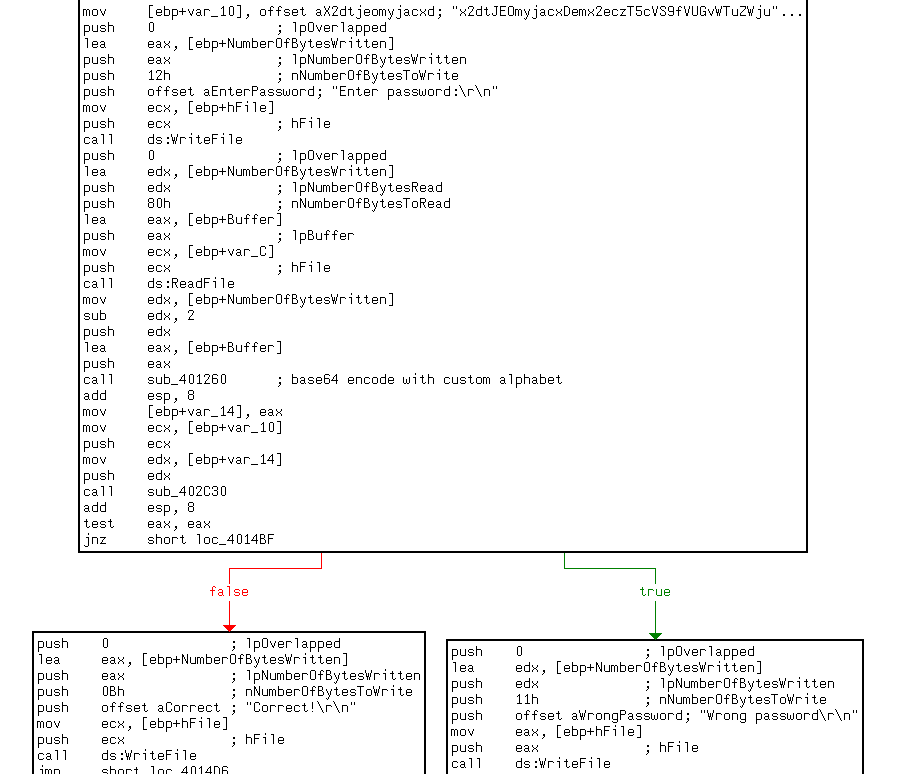

Upon opening the binary in IDA we realize that the program logic is quite simple - the password is base64 encoded and compared to a hardcoded value. The only gotcha here is that the binary is using a custom alphabet to do the encoding.

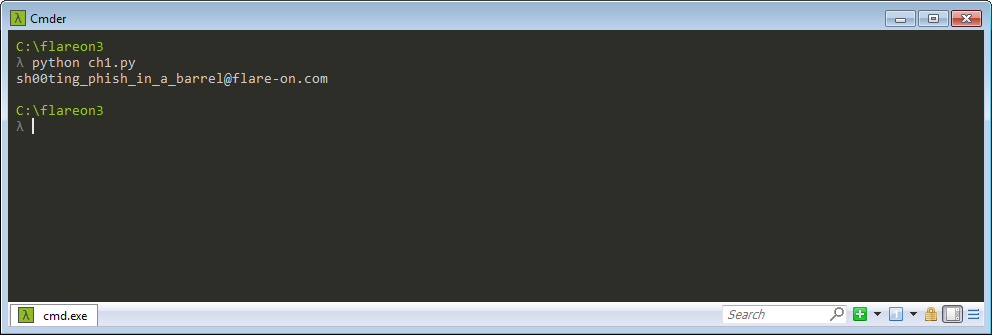

This python script translates between the two alphabets and base64 decodes our flag:

import string

import base64

encoded = 'x2dtJEOmyjacxDemx2eczT5cVS9fVUGvWTuZWjuexjRqy24rV29q'

custom_b64 = 'ZYXABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWzyxabcdefghijklmnopqrstuvw0123456789+/'

std_b64 = 'ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZabcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz0123456789+/'

encoded = encoded.translate(string.maketrans(custom_b64, std_b64))

flag = base64.b64decode(encoded)

print flag

sh00ting_phish_in_a_barrel@flare-on.com

Challenge #2

The second challenge consists of DudeLocker.exe and BusinessPapers.doc files. The .doc file in not a valid

MS Word document and seems to be encrypted with the provided executable.

Stepping through the code with Immunity Debugger, we can see that it only encrypts files which are inside a Briefcase

folder on the current user’s Desktop.

There is also a hard drive volume’s serial number check against a hardcoded value of 7DAB1D35.

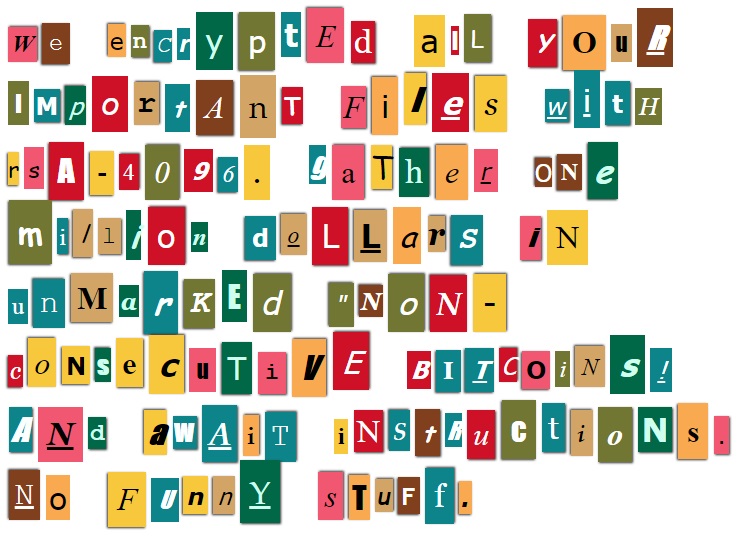

If these checks pass, the locker encrypts all the files inside the Briefcase folder and drops a ve_vant_ze_money.jpg ransom note:

The files are encrypted using standard Microsoft Crypto API. The CryptDeriveKey is used to set up the encryption

key, which in this case is 256 bit AES.

The MSDN states:

The CryptDeriveKey function generates cryptographic session keys derived from a base data value. This function guarantees that when the same cryptographic service provider (CSP) and algorithms are used, the keys generated from the same base data are identical. The base data can be a password or any other user data.

Next, the CryptEncrypt call is used to encrypt the files.

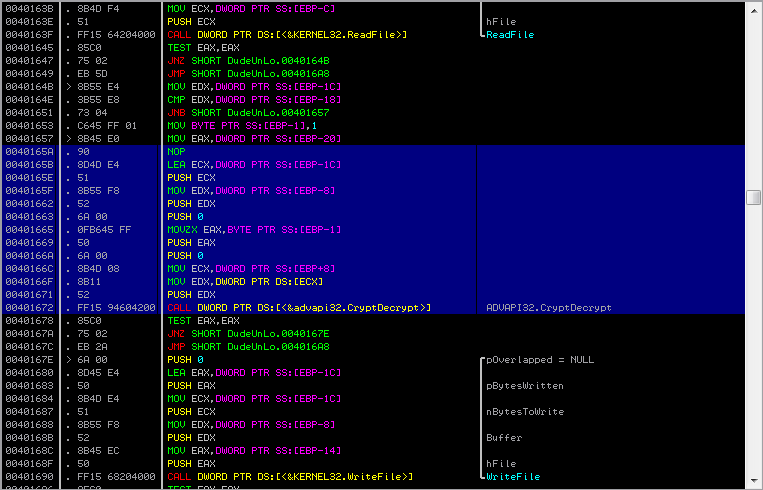

So, given that it’s an AES encryption and the CryptDeriveKey gives us the same key that was used for encryption -

we can replace the CryptEncrypt call with CryptDecrypt and produce a new binary which

decrypts files encrypted with DudeLocker.exe.

So, I added the missing CryptDecrypt call to the binary’s import table and

patched the executable to decrypt the files. The decryption call takes one

parameter less than the encryption one, so I NOP’ed one push to the stack as well:

Next, I modified the C: drive’s serial

number to match the hardcoded one using Sysinternal’s VolumeId.

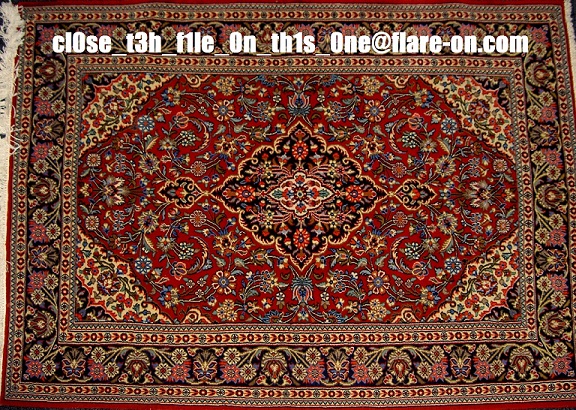

Now, we can use our brand new decryption tool to decrypt the encrypted .doc file, which turns out to be a jpeg with our flag:

cl0se_t3h_f1le_0n_th1s_0ne@flare-on.com

Challenge #3

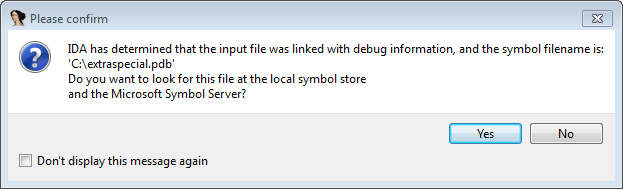

The third challenge is a win32 binary literally called unknown. Upon opening

it in IDA we get our first clue:

After initial analysis and some debugging, we realize that the binary does some

calculations/hashing using the program’s name. There’s also a check for the

letter r in the name of the program. Given all these clues, we must deduce, that the

original binary name must have been extraspecial.exe.

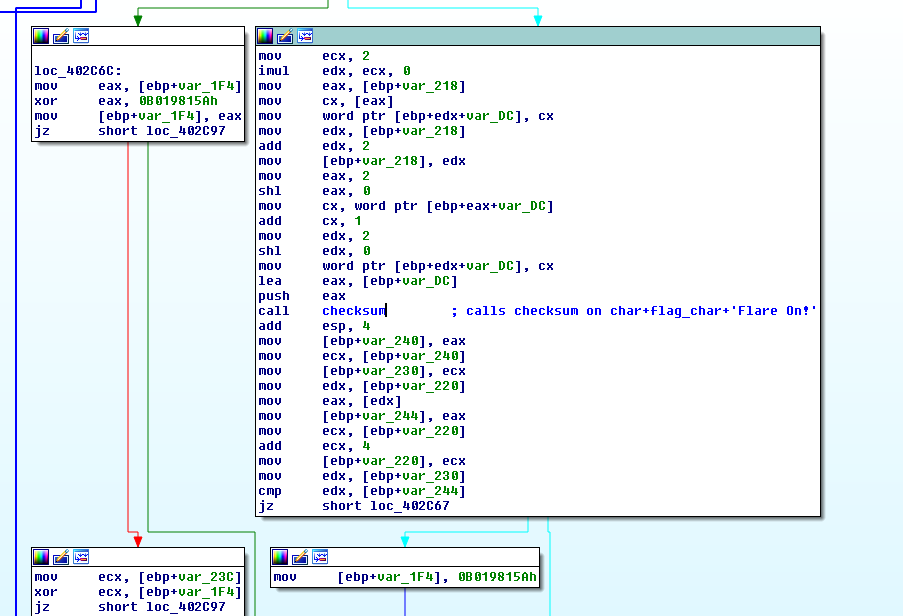

With that out of the way, the interesting part is shown in IDA below:

Here, the program uses our input (which needs to be 0x1A or 26 chars long) to calculate checksums and compares them with the memory values which were computed using the binary’s name. The cheksums are calculated in a loop and use one char of our input per checksum.

I have dumped the 4 * 26 bytes of memory that is used to check our flag from the

debugger and used that to write a python script which finds our flag one char

at a time. A couple notes on the script: First, the hexdump is already in a convenient little endian format and

second, the script uses numpy’s uint32 for the checksum as it perfectly emulates C style overflow of 32 bit

integers (python’s standard behaviour is to extend 32 bit values to 64 bit if they happen to overflow, which

is NOT desireable in this case).

import struct

import numpy as np

import binascii

flare = 'FLARE On!'

start = 0x60

hexdump = '2F3E61EE45EB79DE3D2F1BAFD7BB47879CC49A73AEF5A4C9C1C53246249B02A0595016D65194B7A6BA239DE7CE92AE8A181A99859958E0FE94790C436FF3B91A8124C470CF27BD056F6EFFC47C84775AB37792DDFF3C842544A9DC5F9628E48EC761E92ADA3177A7'

hexdump = hexdump.lower()

hexlist = [hexdump[i*8:(i+1)*8] for i in xrange(0x1a)]

def checksum(str):

result = np.uint32(0)

for char in str:

result = np.uint32(ord(char) + 37 * result)

return result

flag = ''

for i in xrange(0x1a):

for char in xrange(0x20, 0x7f):

concat = chr(char) + chr(start) + flare

sum = checksum(concat)

hexsum = binascii.hexlify(sum)

if hexsum == hexlist[i]:

flag += chr(char)

break

start += 1

print flagOhs0pec1alpwd@flare-on.com

Challenge #4

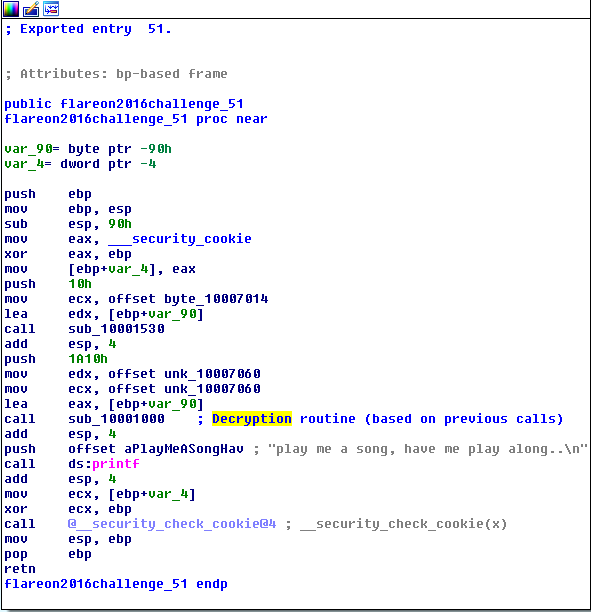

Challenge #4 is a dll file called flareon2016challenge.dll. The dll has 51 exported functions, all of them

exported by the ordinal #.

Export #51 has some kind of decryption call sub_10001000 which is dependant on calling exports 1-48 in some

kind of order prior to calling the #51:

A closer inspection of exports 1-48 reveals that they all return values in the range 1-51 and all of them - different from each other. This suggests that the order of the calls depends on the return values of the calls themselves. So if the #51 was to be called the last, then the previous one would have to be the one returning 51 and so on. Walking backwards all the way, we find that we need to start with the #30 and just call others based on the return value.

One of the easier ways to do that is from a python script:

from ctypes import *

mydll = cdll.LoadLibrary("C:\\flareon2016challenge.dll")

i = 30

while True:

print "Calling: ", i

i = mydll[i]()

if i == 51:

break

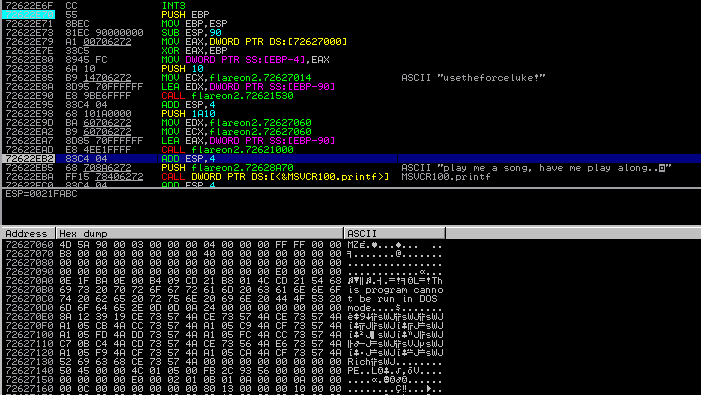

mydll[51]()While debugging, I would insert a time.sleep(10) call before the export #51 itself, to be able to

attach a debugger and trace the decryption. As can be seen from the MZ header, the decrypted blob

is actually an executable:

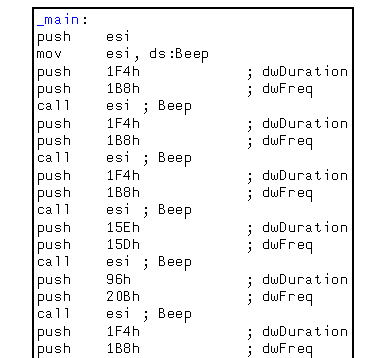

After dumping the exe from memory, it turns out to have our secret melody which provides the parameters for the export #50:

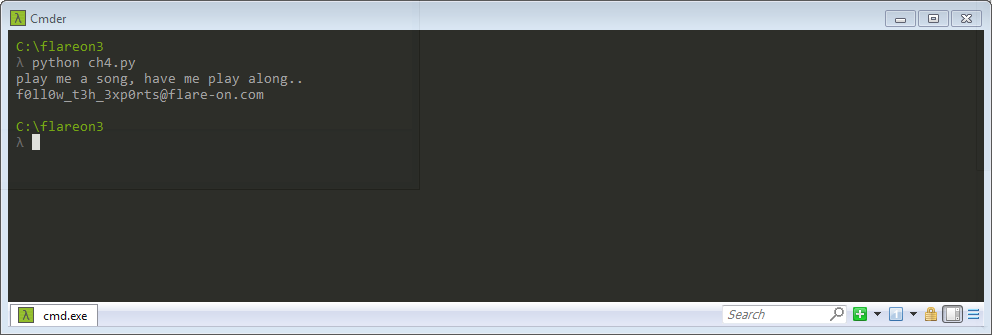

With this information we can finish the script and (after a nice tune) get our flag.

from ctypes import *

mydll = cdll.LoadLibrary("C:\\flareon2016challenge.dll")

i = 30

while True:

i = mydll[i]()

if i == 51:

break

mydll[51]()

mydll[50](0x1B8, 0x1F4)

mydll[50](0x1B8, 0x1F4)

mydll[50](0x1B8, 0x1F4)

mydll[50](0x15D, 0x15E)

mydll[50](0x20B, 0x96)

mydll[50](0x1B8, 0x1F4)

mydll[50](0x15D, 0x15E)

mydll[50](0x20B, 0x96)

mydll[50](0x1B8, 0x3E8)

mydll[50](0x293, 0x1F4)

mydll[50](0x293, 0x1F4)

mydll[50](0x293, 0x1F4)

mydll[50](0x2BA, 0x15E)

mydll[50](0x20B, 0x96)

mydll[50](0x19F, 0x1F4)

mydll[50](0x15D, 0x15E)

mydll[50](0x20B, 0x96)

mydll[50](0x1B8, 0x3E8)

f0ll0w_t3h_3xp0rts@flare-on.com

Challenge #5

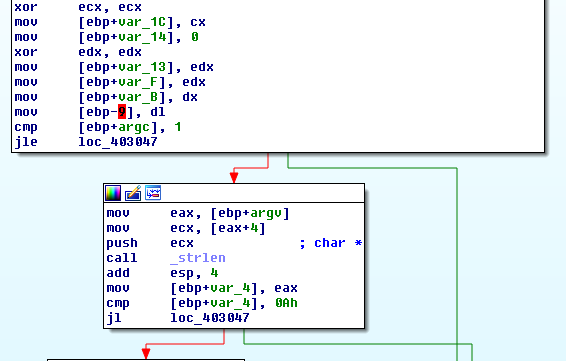

Challenge #5 is a windows binary named smokestack.exe. Initial inspection in

IDA shows that it expects a command line argument that is at least 10

characters long:

Next, the argument is placed in a global array of WORDS at 0x40DF20. Then the

interesting part happens inside the function sub_401610. This function sets

up an index of functions to be called later, initializes some global variables

and executes the main loop:

Inside the loop the program calls sub_401540 which uses previously

initialized index of functions to perform operations on our initial input. Now,

the most called functions seem to be sub_401000 and sub_401080

.text:00401000 push ebp

.text:00401001 mov ebp, esp

.text:00401003 mov ax, word_40DF1C

.text:00401009 add ax, 1

.text:0040100D mov word_40DF1C, ax

.text:00401013 movzx ecx, word_40DF1C

.text:0040101A mov dx, [ebp+arg_0]

.text:0040101E mov word_40DF20[ecx*2], dx

.text:00401026 pop ebp

.text:00401027 retn

.text:00401080 push ebp

.text:00401081 mov ebp, esp

.text:00401083 push ecx

.text:00401084 movzx eax, word_40DF1C

.text:0040108B mov cx, word_40DF20[eax*2]

.text:00401093 mov [ebp+var_4], cx

.text:00401097 mov dx, word_40DF1C

.text:0040109E sub dx, 1

.text:004010A2 mov word_40DF1C, dx

.text:004010A9 mov ax, [ebp+var_4]

.text:004010AD mov esp, ebp

.text:004010AF pop ebp

.text:004010B0 retnThe first function takes an argument and stores it at the end of our global array and the second function does the opposite - returns the last value and decrements the pointer. These functions effectively act like PUSH and POP operations on our global array (smokestack). They could be implemented in python like the following:

def sub_401000(char):

global v3

global key

v3 += 1

key[v3] = char

return v3 + 1

def sub_401080():

global v3

r = key[v3]

v3 -= 1

return rSo, similarly to the functions above, I have implemented all 14 index functions and the surrounding program logic into a huge unpythonic program. The last part shown below uses the implemented functions to calculate the correct argument:

## Key calculation

arg = ''

for i in reversed(xrange(10)):

reset_()

first = sub_401610()

for ch in xrange(0x21, 0x7f):

reset_()

key[i] = ch

r = sub_401610()

if r != first:

arg += chr(ch)

final_key[i] = ch

break

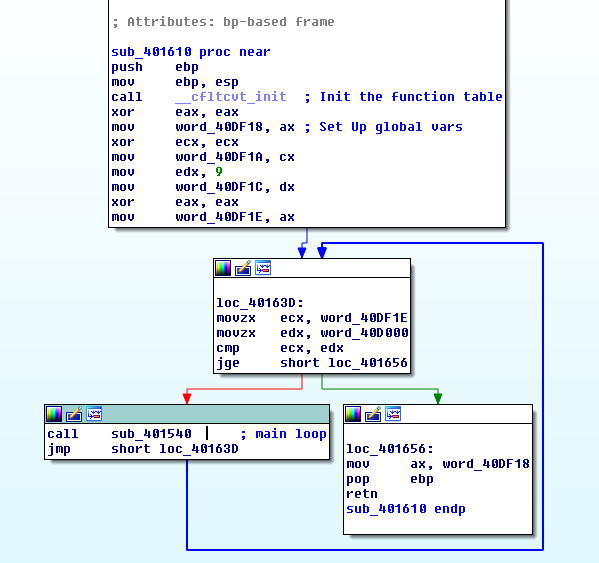

print arg[::-1]Now, the whole script is too big to be posted here (you can find it on github, along with other scripts). The final result:

A_p0p_pu$H_&_a_Jmp@flare-on.com

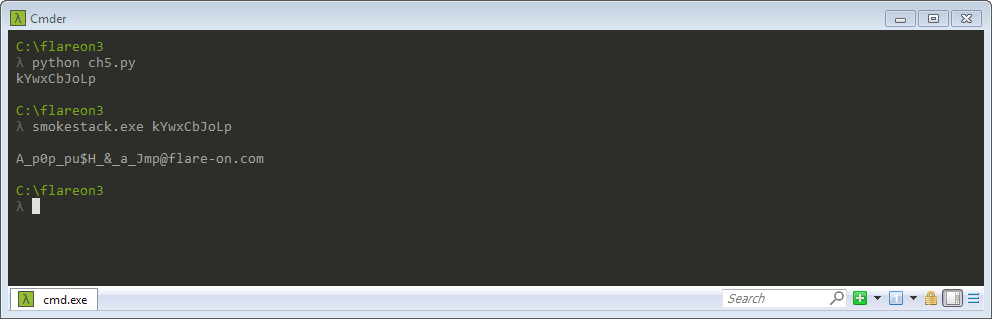

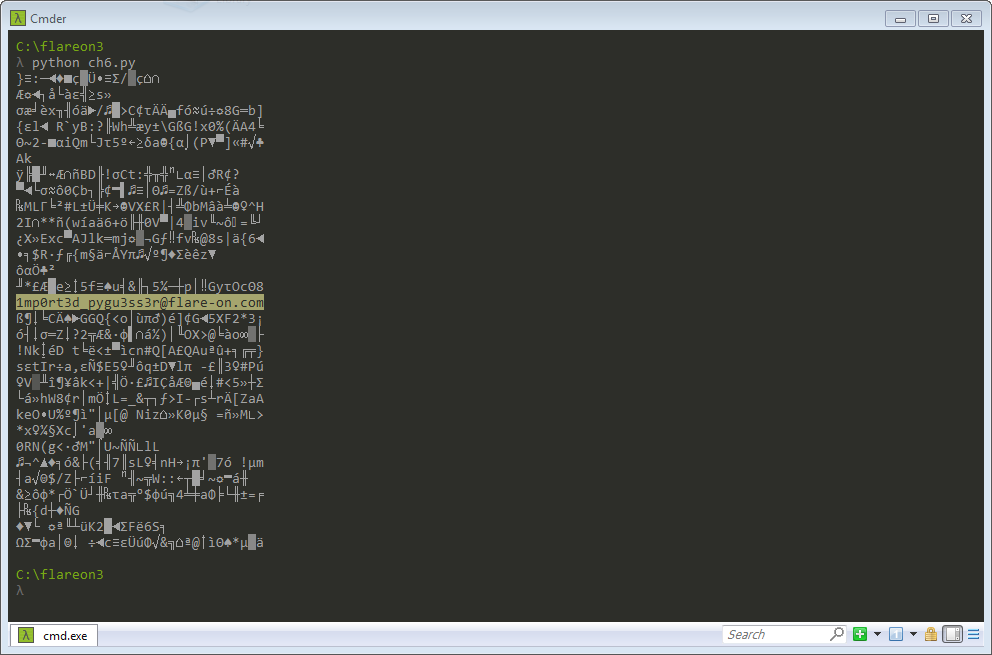

Challenge #6

For #6 we have a windows binary called khaki.exe. When executed - it presents

us with a guessing game:

Initial analysis of the strings shows that it is a binary compiled

with py2exe. Normally, we would decompile the

binary with uncompyle or a similar decompiler and get the python source code.

However, in this case the decompilation fails due to some unknown

modifications in the binary. A quick google search finds a FLARE blog post about this

particular issue. As it turns out, the python bytecode was manually manipulated to

prevent easy decompilation. The blog post goes into great detail about the

issue and provides a tool which enables us to get a clean decompile. With the

help of the provided tool, we get the python source:

import sys, random

__version__ = 'Flare-On ultra python obfuscater 2000'

target = random.randint(1, 101)

count = 1

error_input = 'a'

while True:

print '(Guesses: %d) Pick a number between 1 and 100:' % count,

input = sys.stdin.readline()

try:

input = int(input, 0)

except:

error_input = input

print 'Invalid input: %s' % error_input

continue

if target == input:

break

if input < target:

print 'Too low, try again'

else:

print 'Too high, try again'

count += 1

if target == input:

win_msg = 'Wahoo, you guessed it with %d guesses\n' % count

sys.stdout.write(win_msg)

if count == 1:

print 'Status: super guesser %d' % count

sys.exit(1)

if count > 25:

print 'Status: took too long %d' % count

sys.exit(1)

else:

print 'Status: %d guesses' % count

if error_input != '':

tmp = ''.join((chr(ord(x) ^ 66) for x in error_input)).encode('hex')

if tmp != '312a232f272e27313162322e372548':

sys.exit(0)

stuffs = [67, 139, 119, 165, 232, 86, 207, 61, 79, 67, 45, 58, 230, 190,

181, 74, 65, 148, 71, 243, 246, 67, 142, 60, 61, 92, 58, 115, 240, 226, 171]

import hashlib

stuffer = hashlib.md5(win_msg + tmp).digest()

for x in range(len(stuffs)):

print chr(stuffs[x] ^ ord(stuffer[x % len(stuffer)])),

printAs we can see, the program expects us to guess a random number in a certain number of tries as well as provide a certain bad input (‘shameless plug’ - a reference to the FLARE blog post) for one of those tries. I have reduced this code to only the relevant part, looping through possible number of guesses, one of which produces our flag:

import hashlib

tmp = '312a232f272e27313162322e372548'

stuffs = [67, 139, 119, 165, 232, 86, 207, 61,

79, 67, 45, 58, 230, 190, 181, 74, 65, 148, 71,

243, 246, 67, 142, 60, 61, 92, 58, 115, 240, 226, 171]

for count in xrange(25):

win_msg = 'Wahoo, you guessed it with %d guesses\n' % count

stuffer = hashlib.md5(win_msg + tmp).digest()

s = ''

for x in range(len(stuffs)):

s += chr(stuffs[x] ^ ord(stuffer[x % len(stuffer)]))

print s

1mp0rt3d_pygu3ss3r@flare-on.com

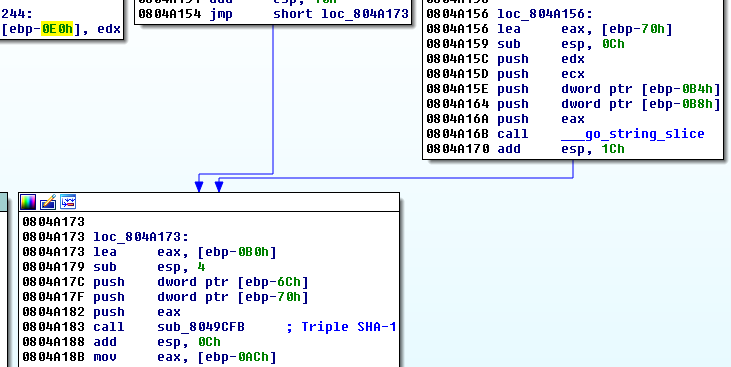

Challenge #7

Challenge #7 is a linux binary named hashes. Upon trying to run the binary

for the first time it becomes evident (missing libgo.so.7) that it was written in Go programming

language. After installing required dependency (libgo7) and setting up remote

linux debugging with IDA, we can dive into the workings of this binary. Now,

analyzing and debugging Go binaries is quite confusing, because of the use of

channels and strange stack manipulations while calling functions. After

fighting with this for a while, we find the interesting parts:

Here, the program slices the program argument (which should be 30 chars long)

into 5 pieces and calculates a triple SHA1 hash on each of them. Later, it compares the results to

effectively hardcoed values (by using a lookup). In order to calculate our

flag, we have to brute force the hashes. The task is quite feasible given that

our inputs are only 6 chars long and there’s a nice limitation on possible

characters inside the program:

A part of the script that cracks the hashes is shown below. We could decrease the cracking time

by using the information that all the flags in this challenge end with @flare-on.com, however,

on my laptop the whole bruteforcing time was ~20min, so not a huge loss there.

def trip_sha1(s):

return hashlib.sha1(hashlib.sha1((hashlib.sha1(s).digest())).digest()).hexdigest()

const = 0x1cd

current = 0x450

hashes = [[],[],[],[],[]]

for h in reversed(xrange(5)):

for b in xrange(20):

byte = blob[current]

current -= 0x1cd

if current < 0:

current += 0x1000

hashes[h] = [byte] + hashes[h]

h_str = [binascii.hexlify(''.join([chr(b) for b in h])) for h in hashes]

alphabet = 'abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz@-._1234'

# We have the hashes, need to crack them

for c1 in alphabet:

for c2 in alphabet:

for c3 in alphabet:

for c4 in alphabet:

for c5 in alphabet:

for c6 in alphabet:

six = ''.join([c1,c2,c3,c4,c5,c6])

if trip_sha1(six) in h_str:

print six, trip_sha1(six)Combining all the cracked pieces together we get the flag:

h4sh3d_th3_h4sh3s@flare-on.com

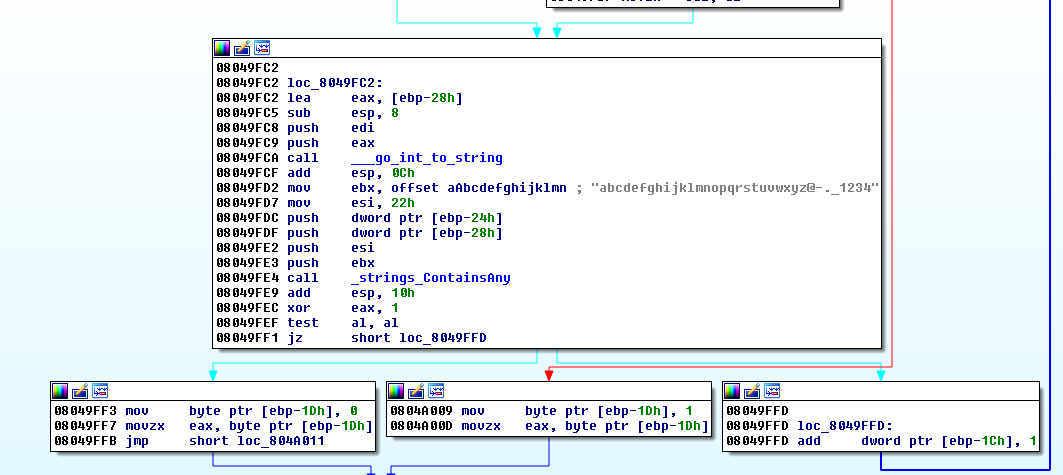

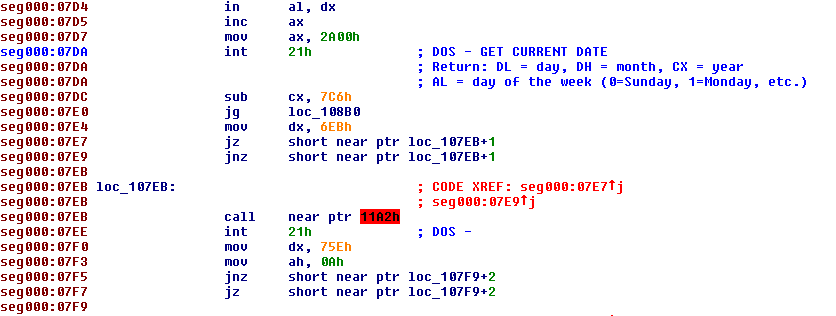

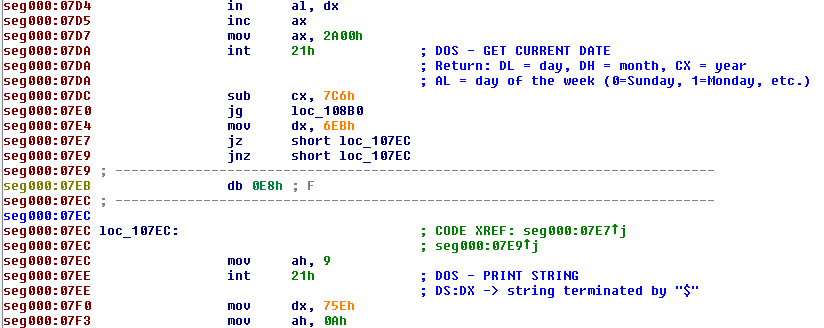

Challenge #8

Challenge #8 is a file called CHIMERA.EXE. This one was a favourite challenge of many participants. It has

a very clever twist which caught many people (myself included) of guard. As it turns out, the binary is both

a valid win32 application as well as a valid DOS 16-bit binary. There are a few subtle clues that point

to that discovery, one of which is the ‘This program cannot not be run in DOS mode.’ message

inside the DOS header. I will skip the 32bit part, as it is a dead end.

To disassemble in 16bit mode, we have to specifically tell IDA to open the file as DOS executable. Inside, we see some self-decrypting code:

seg000:07C6 loc_107C6: ; CODE XREF: seg000:0009j

seg000:07C6 mov cx, 70h ; 'p'

seg000:07C9

seg000:07C9 loc_107C9: ; CODE XREF: seg000:07D2j

seg000:07C9 mov bx, cx

seg000:07CB dec bx

seg000:07CC add bx, bx

seg000:07CE add [bx+7D4h], cx

seg000:07D2 loop loc_107C9

seg000:07D4

seg000:07D4 loc_107D4: ; CODE XREF: seg000:loc_107D4j

seg000:07D4 jmp short near ptr loc_107D4+1

seg000:07D4 ; ---------------------------------------------------------------------------

seg000:07D6 db 0BEh, 0B8h, 0FDh, 29h, 0C9h, 21h, 7Ch, 0E9h, 0C0h, 7

seg000:07D6 db 8, 8Fh, 0C4h, 0, 0B1h, 0EBh, 0FCh, 73h, 0F8h, 74h, 0F5h

seg000:07D6 db 0E7h, 0A7h, 9, 0BFh, 21h, 0ABh, 5Eh, 0F7h, 0B3h, 0F9h

seg000:07D6 db 74h, 0F2h, 73h, 0EFh, 82h, 0B0h, 0CDh, 0Ch, 31h, 0B3h

seg000:07D6 db 74h, 0EAh, 2Ch, 9Ah, 97h, 71h, 26h, 45h, 7, 1Dh, 0E1hI have replicated the decryption routine in a small IDAPython script, which allows a further static analysis into the binary:

import idc

st = idc.SelStart()

cx = 0x70

while cx > 0:

bx = 2 * (cx - 1)

temp = idc.Word(st + bx) + cx

idc.PatchWord(st + bx, temp)

cx -= 1Now the decrypted code shows up inside IDA:

As we can see, the code is still not correct as there a jumps landing in the middle of other instructions, making them invalid. We can fix that quite easily by undefining (‘U’) and redefining instructions as code (‘C’) in IDA. After fixing the first jumps, the code looks like this:

After fixing all the decrypted code, I could analyze the workings of the program. In addition to reading the

disassembly I used a DOSBox debugger to validate my findings and trace parts of the program.

First, CHIMERA checks if the program is running after the year 1990 and exits if that’s the case. We can set the clock back or (as I did) change it inside the debugger. Second, it reads an input string and after encoding it, compares the result to a correct string’s encoded value.

This python script reverses the encoding and finds our flag:

target = [

0x38, 0xE1, 0x4A, 0x1B, 0x0C, 0x1A, 0x46, 0x46, 0x0A,

0x96, 0x29, 0x73, 0x73, 0xA4, 0x69, 0x03, 0x00, 0x1B,

0xA8, 0xF8, 0xB8, 0x24, 0x16, 0xD6, 0x09, 0xCB]

lookup = [

0xFF, 0x15, 0x74, 0x20, 0x40, 0x00, 0x89, 0xEC, 0x5D, 0xC3,

0x42, 0x46, 0xC0, 0x63, 0x86, 0x2A, 0xAB, 0x08, 0xBF, 0x8C,

0x4C, 0x25, 0x19, 0x31, 0x92, 0xB0, 0xAD, 0x14, 0xA2, 0xB6,

0x67, 0xDD, 0x39, 0xD8, 0x5F, 0x3F, 0x7B, 0x5C, 0xC2, 0xB2,

0xF6, 0x2E, 0x75, 0x9B, 0x61, 0x94, 0xCF, 0xCE, 0x6A, 0x98,

0x50, 0xF2, 0x5B, 0xF0, 0x45, 0x30, 0x0E, 0x38, 0xEB, 0x3B,

0x6C, 0x66, 0x7F, 0x24, 0x3D, 0xDF, 0x88, 0x97, 0xB9, 0xB3,

0xF1, 0xCB, 0x83, 0x99, 0x1A, 0x0D, 0xEF, 0xB1, 0x03, 0x55,

0x9E, 0x9A, 0x7A, 0x10, 0xE0, 0x36, 0xE8, 0xD3, 0xE4, 0x32,

0xC1, 0x78, 0x07, 0xB7, 0x6B, 0xC7, 0x70, 0xC9, 0x2C, 0xA0,

0x91, 0x35, 0x6D, 0xFE, 0x73, 0x5E, 0xF4, 0xA4, 0xD9, 0xDB,

0x43, 0x69, 0xF5, 0x8D, 0xEE, 0x44, 0x7D, 0x48, 0xB5, 0xDC,

0x4B, 0x02, 0xA1, 0xE3, 0xD2, 0xA6, 0x21, 0x3E, 0x2F, 0xA3,

0xD7, 0xBB, 0x84, 0x5A, 0xFB, 0x8F, 0x12, 0x1C, 0x41, 0x28,

0xC5, 0x76, 0x59, 0x9C, 0xF7, 0x33, 0x06, 0x27, 0x0A, 0x0B,

0xAF, 0x71, 0x16, 0x4A, 0xE9, 0x9F, 0x4F, 0x6F, 0xE2, 0x0F,

0xBE, 0x2B, 0xE7, 0x56, 0xD5, 0x53, 0x79, 0x2D, 0x64, 0x17,

0x95, 0xA7, 0xBD, 0x7C, 0x1D, 0x58, 0x93, 0xA5, 0x65, 0xF8,

0x18, 0x13, 0xEA, 0xBC, 0xE5, 0xF3, 0x37, 0x04, 0x96, 0xA8,

0x1E, 0x01, 0x29, 0x82, 0x51, 0x3C, 0x68, 0x1F, 0x8E, 0xDA,

0x8A, 0x05, 0x22, 0x72, 0x49, 0xFA, 0x87, 0xA9, 0x54, 0x62,

0xC6, 0xAA, 0x09, 0xB4, 0xFD, 0xD6, 0xD1, 0xAC, 0x85, 0x11,

0x47, 0x3A, 0x9D, 0xE6, 0x4D, 0x1B, 0xCC, 0x52, 0x80, 0x23,

0xFC, 0xED, 0x8B, 0x7E, 0x60, 0xCD, 0x6E, 0x57, 0xBA, 0xDE,

0xAE, 0xCA, 0xC4, 0x77, 0x0C, 0x4E, 0xD4, 0xD0, 0xC8, 0xE1,

0xB8, 0xF9, 0x26, 0x90, 0x81, 0x34]

def ROL(data, shift, size=8):

shift %= size

remains = data >> (size - shift)

body = (data << shift) - (remains << size )

return (body + remains)

before = []

before.append(target[0] ^ 0xC5)

for i in xrange(1, 0x1A):

before.append(target[i] ^ target[i - 1])

before.append(0x97)

rflag = ''

for i in reversed(xrange(0x1A)):

dl = before[i + 1]

bx = ROL(dl, 3)

dl = lookup[lookup[bx]]

ch = dl ^ before[i]

rflag += chr(ch)

print rflag[::-1]retr0_hack1ng@flare-on.com

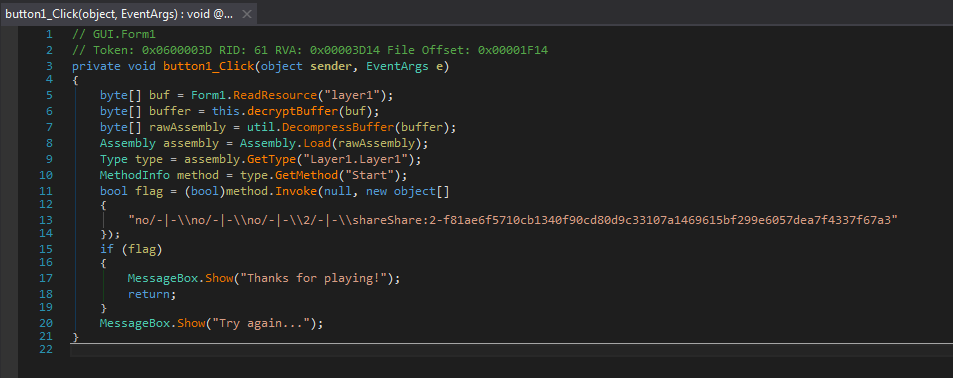

Challenge #9

Challenge #9 is a .NET binary named GUI.exe. Running it gives us:

One of the best tools for reversing .NET binaries is dnSpy. Upon opening the file in dnSpy, we see that the

code has been obfuscated with ConfuserEx 1.0. The button click handler function looks like this:

private void button1_Click(object sender, EventArgs e)

{

byte[] buf = Form1.ReadResource(<Module>.\u206F\u202C\u206B\u202E\u200F\u206E\u202E\u206B\u202D\u206D\u200F\u206F\u200F\u200F\u202B\u202C\u200E\u206B\u202C\u202A\u202E\u206D\u206C\u200E\u206C\u206E\u200B\u200F\u206F\u200E\u202A\u206F\u206C\u200B\u206B\u206A\u206B\u202C\u206B\u206E\u202E<string>(282000140u));

byte[] buffer = this.decryptBuffer(buf);

byte[] rawAssembly = util.DecompressBuffer(buffer);

Assembly assembly = Assembly.Load(rawAssembly);

Type type = assembly.GetType(<Module>.\u202C\u200C\u200F\u202E\u202A\u200E\u202A\u206D\u206F\u200D\u206C\u202C\u200C\u206D\u200C\u206D\u206E\u200E\u200C\u202C\u200F\u206C\u206C\u200D\u200E\u206C\u200D\u202D\u206A\u206E\u200D\u202A\u200B\u206D\u206B\u200D\u206A\u206B\u206E\u206F\u202E<string>(370292149u));

MethodInfo method = type.GetMethod(<Module>.\u202A\u202C\u206D\u202C\u202A\u206C\u202C\u202B\u206D\u202B\u200F\u202C\u200B\u200F\u206E\u200D\u200C\u202C\u206B\u200E\u200D\u202E\u206C\u206A\u202C\u200F\u200D\u202A\u206C\u202A\u202D\u200B\u200E\u206F\u202B\u206D\u200F\u206E\u202A\u206E\u202E<string>(547307959u));

bool flag = (bool)method.Invoke(null, new object[]

{

<Module>.\u202A\u202C\u206D\u202C\u202A\u206C\u202C\u202B\u206D\u202B\u200F\u202C\u200B\u200F\u206E\u200D\u200C\u202C\u206B\u200E\u200D\u202E\u206C\u206A\u202C\u200F\u200D\u202A\u206C\u202A\u202D\u200B\u200E\u206F\u202B\u206D\u200F\u206E\u202A\u206E\u202E<string>(292816780u)

});

if (flag)

{

MessageBox.Show(<Module>.\u202D\u202A\u202E\u206C\u202B\u200F\u206B\u202A\u206C\u200D\u200D\u200C\u202B\u206F\u206F\u202C\u206F\u206E\u206D\u206C\u206D\u206F\u206D\u202B\u202C\u200C\u200E\u206B\u200E\u200D\u202C\u206C\u206B\u206E\u200C\u202D\u202E\u200C\u200C\u200C\u202E<string>(3452886671u));

return;

}

MessageBox.Show(<Module>.\u206B\u206A\u200E\u202B\u200E\u202B\u202C\u200F\u202E\u202D\u202B\u200F\u206E\u202B\u206B\u202B\u202A\u206E\u206C\u202B\u202E\u206F\u202C\u200C\u200E\u206A\u202B\u202E\u202D\u200D\u202C\u206E\u202D\u206B\u206D\u206C\u202B\u202D\u206C\u206A\u202E<string>(458656109u));

I have found a few tools that help with deobfuscating ConfuserEx, namely deDot and some tools produced by the

members of the tuts4you forum. With the help of these tools, we can deobfuscate the code to something readable:

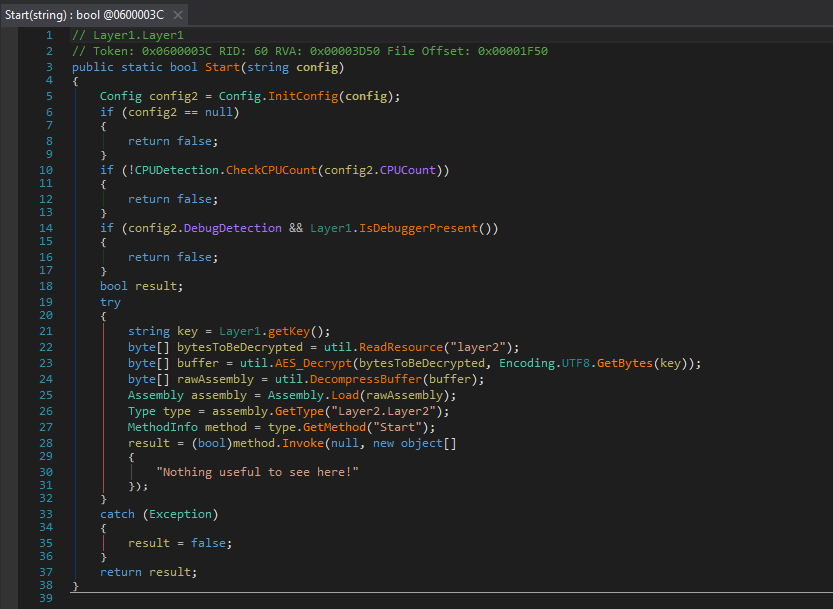

As we can see, the program dynamically decrypts Layer1.dll, loads the assembly and calls the Start function. At this

point we can dump the Layer1.dll and deobfuscate it - to make it more readable:

The code here checks for a debugger with IsDebuggerPresent() (this one is bypassed with dnSpy by default) and

checks that cpuCount is > 1 (a simple VM check, as most VM’s run with 1 virtual CPU). Afterwards, there is

a getKey() function which enumerates folders in the current directory and looks for a folder named sharing.

So, we give our VM 2 CPUs and create a ‘sharing’ folder.

Now, the programs decrypts and loads Layer2.dll.

Similarly, Layer2 checks for VM usage with a WMI query select * from win32_videocontroller (this can be

bypassed with a debugger). Later, the getKey function looks for the registry key secret under HKEY_CURRENT_USER.

After creating the key in the registry, we proceed to Layer3.

Similar to previous checks, this layer checks

for the existence of the user shamir on the system. After satisfying that check we get a decrypted picture:

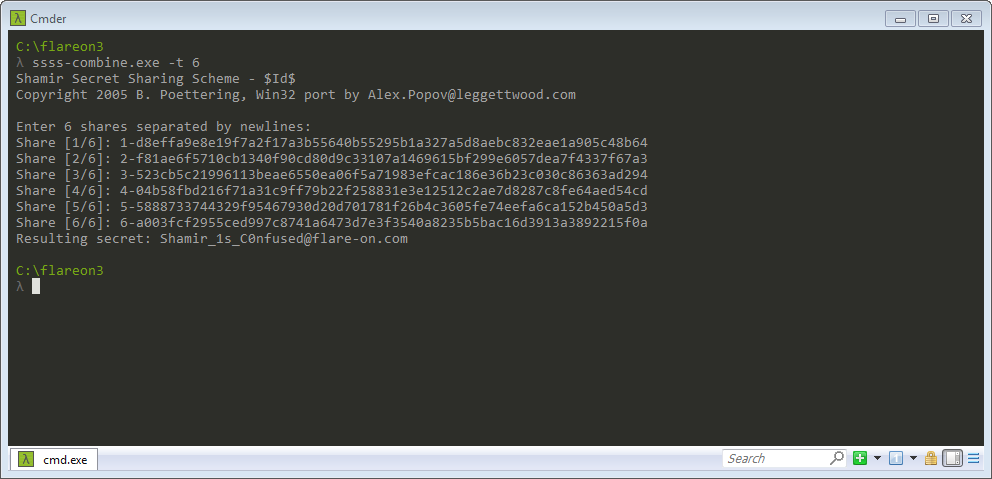

In addition to the decrypted picture, a ssss-combine.exe binary gets placed

in the folder where the GUI.exe is running from. This binary is a windows

implementation of the Shamir's Secret Sharing Scheme. To get our flag, we

need to combine all 6 shares using ssss-combine.exe. We can dump the first

5 shares from running binary’s memory (after successfuly reaching the decoded

picture part) and the 6th one is inside the decoded png.

Combining all the shares gives us the flag:

Shamir_1s_C0nfused@flare-on.com

Challenge #10

Unlike the previous challenges, this one is not an executable file. Instead we

are given a pcap file called flava.pcap.

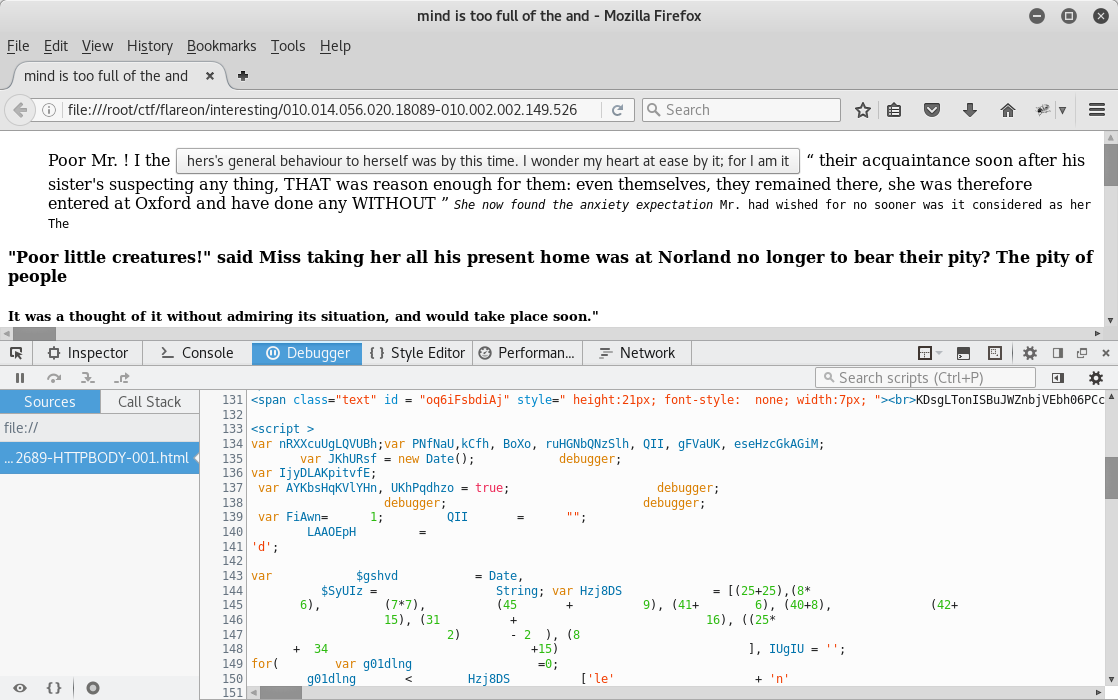

The interesting part of the pcap is the stream 233 (tcp.stream == 233 in wireshark). It starts with a GET request to a html page with a bunch of obfuscated javascript:

After cleaning up parts of the code, we can analyze what it does. The end goal of the initial javascript is to decode and load layer2. The loading happens inside a try/catch block, which suppresses any faulty decoding:

try {

if (FiAwn == 1) {

var U7weQ = new Function(i9mk);

U7weQ();

FiAwn = 2

}

else {

var O0fdFD = new Function(i9mk);

O0fdFD(i9mk)

}

} catch (lol) {}

There are a few checks in the code which prevent a successful decode. The first one is a

ScriptEngineBuildVersion check and a couple of date checks. After fixing those checks to always return

the correct values, we decode layer2 (partial view):

function k() {

String['prototype']['kek'] = function(a, b, c, d) {

var e = '';

a = unescape(a);

for (var f = 0; f < a['length']; f++) {

var g = b ^ a['charCodeAt'](f);

e += String['fromCharCode'](g);

b = (b * c + d) & 0xFF;

}

return e;

}, String['prototype'][''['kek']('%0B%5Ei', 108, 41, 237)] = function() {

return ''['kek']('%C96%E4B%3Ei_%83n%C1%82%FB%DC%01%EAA+o', 175, 129, 43);

}, String['prototype'][''['kek']('6%87%24', 94, 13, 297)] = function() {

return ''['kek']('4%94%0D%86%7BVXJ%AD%1C%87%0E%FE%C0%DA%D2%20%82%01%ACWAJd%B6%06%8D/', 92, 33, 31);

};

try {

m();

var a = l();

} catch(zzzzz) {}

}

try {

k();

} catch (z) {}

The end goal of this layer is similar to the first one - to load another decoded javascript. After bypassing a few checks for Kaspersky products, we decode the 3rd layer (also partial view):

var Il1Ib = Math, Il1Ic = String, Il1IIll1a = JSON, Il1IIll1b = XMLHttpRequest;

var Il1Ie = ''['lol']('9%E44%BC%1Ap', 90, 9, 97),

Il1If = ''['>_<']('%D0%94%18F%A5%C0', 162, 5, 199),

Il1Ig = ''['OGC']('%B7%5By4%B6%B4w', 199, 33, 147),

Il1Ih = ''['-Q-']('%B7j%16%9E%04%88%E4%3Ej', 199, 17, 225),

Il1I = ''['>_O']('%DB%FCy%7D%E1', 168, 129, 247),

Il1Ii = ''['o3o']('%C4J%13sI%F7%3D', 173, 5, 195),

Il1Ij = ''['Orz']('%D6%E4zP%20%EC', 181, 9, 47),

Il1Ik = ''['Orz']('F%92%1C%D5%DF%02', 52, 65, 191),

Il1Il = ''['^_^']('%3Eq%01%F4%C7G%FB%B7%F34%A2%94', 88, 65, 171),

Il1Im = ''['^_^']('%DFu%5C_c', 190, 33, 135),

Il1In = ''['lol']('%FA%5E%1A%F6V%9F', 150, 5, 77),

Il1Io = ''['>_<']('%F9S%F8%AE%BB%11%89q', 141, 65, 111),

Il1Ip = ''['OGC']('%03%F7%B7%B7o%A4%06%D49%03', 96, 9, 63),

Il1Iq = ''['O_o']('%C3%BE%10%C3+', 165, 129, 173),

Il1Ir = ''['lol']('%D4%1B%E7M', 167, 33, 235);

var Il1IbbAa = ''['>_O']('%10%8D%81%CE%17%A9y9%5B%F0%3Bx%DE%3FC%EB%85%FD%EE%8A%80%FAy%9D%CC%A11%D4KH%23%AF6.%84%5D%28%D8%06dg%24%26%E0%E3%8E0s%A8%1F%B1%10%AF%1B%09%03%E3%02%EBR%5C%A9%13%E5%E3O%3E%BC%E6d%29%C7*3%C1C%A9%FA%13%D2t%B0thY%86O3', 65, 5, 147);

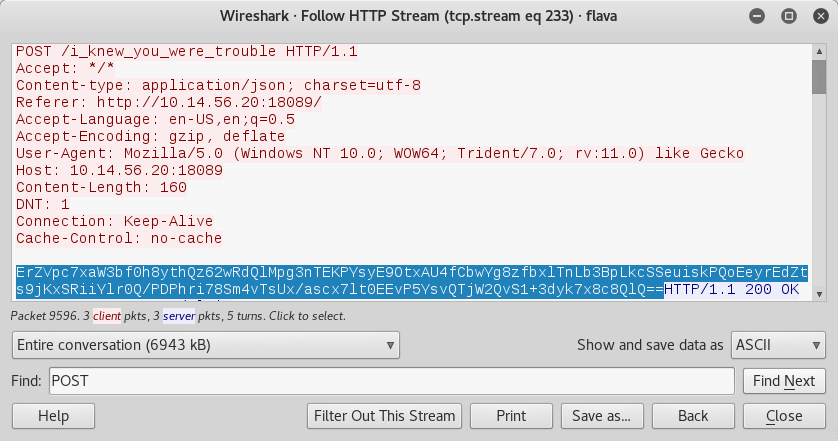

Now, here the interesting function is Il1Iza() which sends an HTTP POST request that can be seen in the pcap.

A javascript dictionary d is RC4 encrypted with the key flareon_is_so_cute and base64 encoded.

The POST request that the code needs to make is seen here:

With that in mind, we can reverse the dictionary value using this python script:

import base64

import binascii

key = 'flareon_is_so_cute'

target = 'ErZVpc7xaW3bf0h8ythQz62wRdQlMpg3nTEKPYsyE9OtxAU4fCbwYg8zfbxlTnLb3BpLkcSSeuiskPQoEeyrEdZts9jKxSRiiYlr0Q/PDPhri78Sm4vTsUx/ascx7lt0EEvP5YsvQTjW2QvS1+3dyk7x8c8QlQ=='

def rc4(data, key):

"""RC4 encryption and decryption method."""

S, j, out = range(256), 0, []

for i in range(256):

j = (j + S[i] + ord(key[i % len(key)])) % 256

S[i], S[j] = S[j], S[i]

i = j = 0

for ch in data:

i = (i + 1) % 256

j = (j + S[i]) % 256

S[i], S[j] = S[j], S[i]

out.append(chr(ord(ch) ^ S[(S[i] + S[j]) % 256]))

return "".join(out)

target_hex = base64.b64decode(target)

length = len(target_hex)

s = ''

for i in xrange(length):

for char in xrange(0x20, 0x7f):

current = s + chr(char)

if rc4(current, key)[i] == target_hex[i]:

s += chr(char)

break

print sroot@kali:~# python rc4.py

{"g":"91a812d65f3fea132099f2825312edbb","A":"16f2c65920ebeae43aabb5c9af923953","p":"3a3d4c3d7e2a5d4c5c4d5b7e1c5a3c3e"}

root@kali:~#Those parameters represent Angler’s implementation of the Diffie-Hellman protocol to deliver encrypted shellcode.

The base64 encoded response contains the missing B parameter, which enables the receiver to calculate the

private key and decode the payload. An excellent analysis of the whole process was done by Kaspersky Labs

in this post. They provide a Java program which enables us to retrieve the private key that was used.

Plugging in our values into the program (and several hours later) we get:

... snip ...

[i] Processing 88000001

[i] Processing 89000001

[i] Processing 90000001

[i] Processing 91000001

[i] Processing 92000001

[i] Processing 93000001

[i] Processing 94000001

[13449667480594038]

24c9de545f04e923ac5ec3bcfe82711fWith this key we can decode the received payload which contains some javascript and has the key HEAPISMYHOME

for part2 (flash):

alert("Congratz! Wooohooooo, you've done it!\n\nGoing thus far, you have already acquired the basic skillset of analyzing EK's traffic as well as any other web attacks along the way. You should be proud of yourself!\n\nIt is not the end though; it's only the beginning of our exciting journey!\n\nNow would be a good time to take a breather and grab some beer, coffee, redbull, monster, or water.\n\n\n\nClick 'OK' when you're ready to show us what you're made of!");

alert("Cool, seems like you're ready to roll!\n\n\n\nThe key for part2 of the challenge is:\n'HEAPISMYHOME'\n\n\n\nYou will need this key to proceed with the flash challenge, which is also included in this pcap.\n\nGood luck! May the force be with you!");

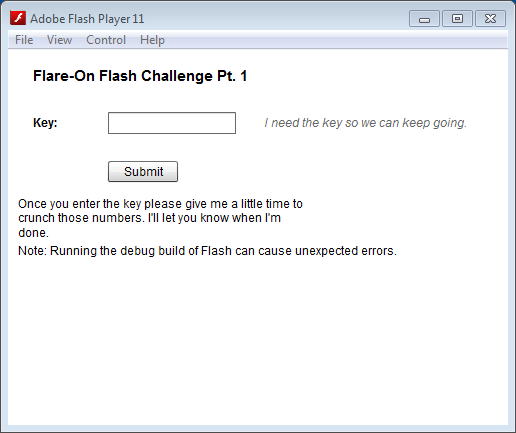

The flash file (which we extracted from the pcap) looks like this:

After entering the key a few messages pop up, but nothing visible happens. We decompile the flash code with the help of JPEXS decompiler. Inside, we find a loader function:

public function d3cryp7AndL0ad(param1:String) : void

{

var _loc2_:Loader = new Loader();

var _loc3_:LoaderContext = new LoaderContext(false,ApplicationDomain.currentDomain,null);

var _loc4_:Class = Run_challenge1;

var _loc5_:ByteArray = pr0udB3lly(ByteArray(new _loc4_()),param1);

var _loc6_:String = "1172ca0ede560b08d97b270400347ede";

if(MD5.hashBytes(_loc5_) == _loc6_)

{

this.loaded = true;

_loc2_.loadBytes(_loc5_);

}

}This function decodes another flash file and loads it into memory. JPEXS is actually capable of dumping

loaded flash files from memory. Using this functionality we dump the loaded flash file onto disk.

It turns out the dumped SWF is obfuscated with secureSWF. Loading this file into JPEXS again and

deobfuscating, we get a somewhat readable AS3 code:

... snip ...

var _loc1_:Object = this.root.loaderInfo.parameters;

if(_loc1_.flare == "On")

{

_loc2_ = new Loader();

_loc3_ = new LoaderContext(false,this.root.loaderInfo.applicationDomain,null);

this.var_1 = new Array();

this.var_4 = new ByteArray();

this.var_39 = _loc1_.x;

this.var_5 = _loc1_.y;

... snip ...From this snippet we can see that this code requires flashvars named flare, x and y passed to it.

The code actually uses the x value as a key to RC4 decode some encoded blobs inside the file and y as

an index to combine and load another SWF from the decoded data.

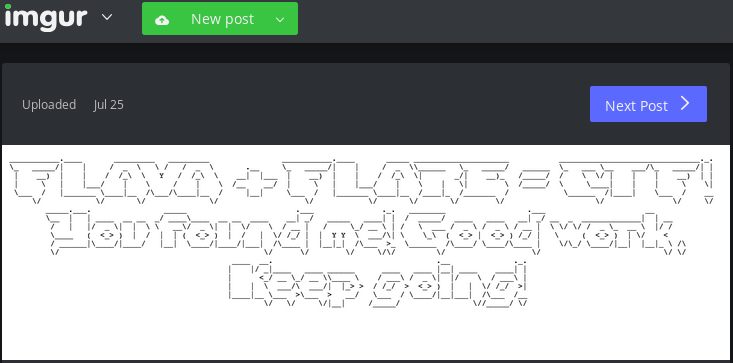

Looking closer at the encoded blobs, it seems that two of them are completely unused inside the decryption

routine. One of them has and interesting refercence to imgur - Int3lIns1de_t3stImgurvnUziJP. It references

an image available at http://imgur.com/vnUziJP

So, at this point we have two unused encrypted blobs of data and an image which actually is the decryption of one

of them. Given this and assuming the same RC4 encryption key for both of them, we can actually get the

plain text by XOR-ing all of them together. The result gives us the x and the y:

x: 1BR0K3NCRYPT0FTW y: 47:14546,46:1617,35:239,4:47,35:394,3:575,32:4,49:4 ... snip ...With these parameters we can load the last decrypted SWF in memory and dump it from there. For some strange reason

I was unable to view the last flash file in JPEXS, so I traced it using Sulo (pin instrumentation plugin for flash).

Inside the trace we get the decoding of our flag char by char:

flash.utils::ByteArray/writeByte ()

this: 0x3e63c90

arg 0: 0x61 : int

Returned: 0x4 : void (call depth: 1)

flash.utils::ByteArray/writeByte ()

this: 0x3e63c90

arg 0: 0x6e : int

Returned: 0x4 : void (call depth: 1)

flash.utils::ByteArray/writeByte ()

this: 0x3e63c90

arg 0: 0x67 : int

Returned: 0x4 : void (call depth: 1)Combining all the arg 0 values, we get the flag:

angl3rcan7ev3nprim3@flare-on.com